Essay

Blue is nice, Red is better

Fanny Zaman, June 2022

Throughout history, every mass medium, from written text to images and posters, from radio to television, whether interactive or not, has attempted to seduce us. Politics and commercial enterprises exploit these applications within our so-called attention economy. How does this form of manipulative mass communication influence public opinion and ultimately shape our idea of democracy?

Marshall McLuhan (1911–1980), a key founder of contemporary media theory, coined the phrase The Medium is the Message in his book Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964). McLuhan aimed to demonstrate that the medium itself significantly shapes the meaning of a message. Later, he transformed the phrase into the title The Medium Is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects (1967). McLuhan used the term massage to indicate the effect that each medium has on our senses. The medium—whether television, radio, or newspapers—massages, independent of content, human perception and public opinion.

Influencing the subconscious through media appears to be the key to shaping our current attention economy.

Commercial enterprises and political actors alike seek to massage, influence, and win over the public. The former is known as advertising, while the latter is called propaganda. Adam Curtis explores the history of both in his four-part documentary The Century of the Self (2002). The documentary centers on the discovery of the subconscious during the interwar period in Vienna by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) and its use in influencing free will. Freud himself witnessed the horrors and chaos leading up to World War II. He saw an uncontrollable mass expressing its deepest and darkest forces — its unconscious drives. Controlling these unconscious drives became the goal of the next generation of political and corporate psychologists. With increasing knowledge, they became more adept at manipulating our subconscious, laying the foundation for today’s attention economy.

Freud’s nephew, Edward Bernays (1891–1995), applied psychoanalysis to public relations in the United States. One of his first moves was to rebrand the pejorative term propaganda into the much more positive-sounding Public Relations (PR). He inspired both the tobacco industry and U.S. President Herbert Clark Hoover (1929–1933), as well as Nazi Germany’s Minister of Propaganda, Paul Joseph Goebbels. They shared an interest in Bernays’ ideas, which he expressed in his essay The Engineering of Consent (1947). The essay’s premise was that the public consists of irrational beings, driven by libidinal forces, barely capable of processing factual information. Therefore, information had to be communicated primarily through symbols. By appealing to universal human emotions and desires, the public was effectively massaged via the mass media of the time. One example of Bernays’ application of psychoanalysis was his Torches of Freedom (1929) campaign for the American Tobacco Company. At that time, smoking was primarily a male activity. Seeing the market potential among women, the company enlisted Bernays to reach them. Bernays decided to break the social taboo of women smoking in public by staging an event. He hired both women and photographers to orchestrate a smoking women’s delegation during New York’s annual public Easter Sunday Parade. Through mass media, the public perceived the staged smoking delegation as a protest for gender equality. Bernays thus manipulated a public mass event, staging a protest that the media and, in turn, the general public would naturally pick up on. In doing so, Bernays likely organized the very first Flash Mob.

Through the Marshall Plan, initiated for Europe’s post-World War II reconstruction, public relations also reached Europe. During the Cold War, Western Europe came under American influence, and PR became a widespread term and method for both governments and commercial enterprises to massage public opinion through psychology. Bernays’ vision in PR was fundamentally based on the idea that the public should be treated as irrational beings incapable of processing factual information. This stands in stark contrast to the democratic ideal of humanism, which holds that citizens should be informed and guided by reason.

A living being (rat, pigeon, or human) is placed in the box, where it must learn to activate levers or respond to light or sound stimuli for rewards.

A generation later, Freud’s ideas about the subconscious evolved into practical applications. Burrhus Frederic Skinner (1904–1990), an influential American psychologist, developed such applications. Skinner became known as the founder of radical behaviorism. He developed operant conditioning, which became widely known as the Skinner box. In this setup, an animal (rat or pigeon) is placed inside a box where it must learn to activate levers or respond to light or sound stimuli to receive a reward. The reward could be food or the removal of harmful stimuli, such as a loud alarm. Radical behaviorism no longer operates according to the humanistic ideal, where individuals seek to understand information. Humanism assumes the ideal of a rational being who makes conscious choices. Radical behaviorism, on the other hand, primarily massages the body, installing unconscious behaviors through a system of rewards and punishments.

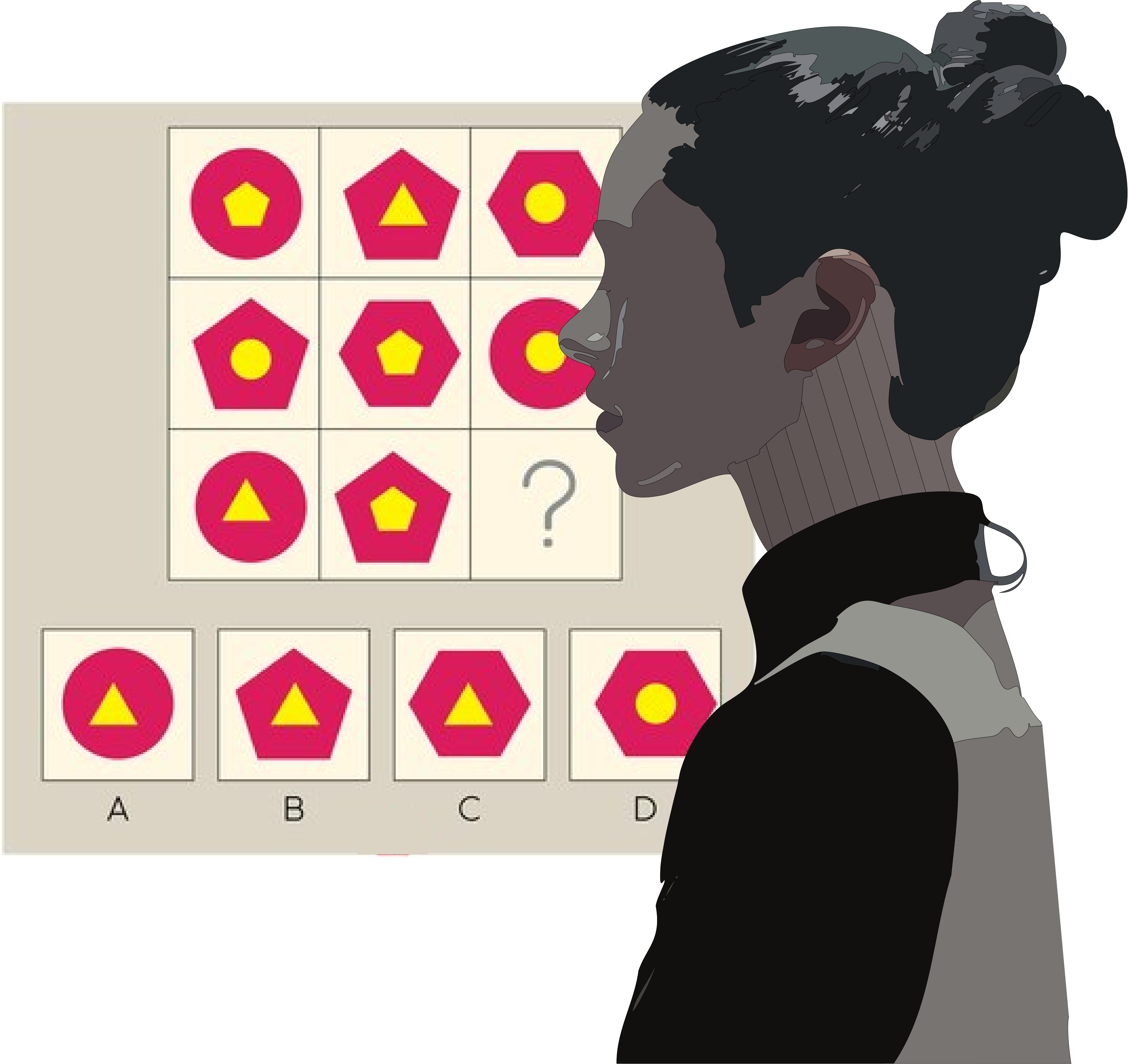

Journalist Koen Haegens, in De Groene Amsterdammer (2022), lists ten techniques that governments and commercial enterprises use today to seduce, addict, and streamline the public. Techniques based on operant conditioning and the engineering of consent include: "Overwhelm the user with social validation," "Exploit FOMO (fear of missing out)," and "Blue is nice, red is better." The Information Industry (Big Tech) skillfully applies these psychological techniques through interactive and social media, transforming them into our current attention economy.

Governments and commercial enterprises today eagerly employ gamification to manipulate human behavior. Gamification consists of game principles and play techniques applied in a non-game context within a digital environment. It is currently trending in educational and healthcare reform and cost-saving strategies.

‘The fun factor will ensure that citizens show less resistance to displaying the desired behavior.’

The ambitions of the Flemish government in its political gamification program were notably articulated by Cathy Coudyser (N-VA) in 2019. She stated in the Flemish Parliament: ‘Gamification’ ‘can be applied on a large scale by creating a new game that steers human behavior.’ and ‘Techniques from the gaming world can increase the effectiveness and efficiency of policy.’ ‘The government can steer citizens’ behavior in the desired direction through the use of game elements and techniques.’ ‘The fun factor will ensure that citizens show less resistance to displaying the desired behavior.’ dixit Cathy Coudyser.

Sources

- McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding Media, The Extensions of Man. Canada: Signet Books

McLuhan, M., Quentin, F. (1967). The Medium Is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects. Canada: Bantam Books, Inc.

Curtis, A. (2002). The Century of the Self. UK: BBC

Bernays, E. (1969). The Engineering of Consent. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Haegens, K. (2022, 23 maart). We zijn geen slaven. De Groene Amsterdammer nr.12, 34-39

SCHRIFTELIJKE VRAAG nr. 30 van CATHY COUDYSER datum: 8 november 2019 aan JAN JAMBON Gamification